Myth of Persephone and the symbolism of seasons

Persephone, the Queen of the Underworld*, was a figure of Greek mythology. The Myth of Persephone is often refered to as the Myth of Demeter, or the rapt of Persephone, because one of the elements of the tale is her lack of ability to decide her own fate (she is depicted as naive, a sort of doll placed in the middle of the guardianship of Demeter and the love of Hades).

(*) The Underworld was the kingdom of the dead, located somewhere beneath the earth -you could find entrances throught caves, for example-, and it was ruled by Hades. The Underworld is sometimes refered simply as Hades. The Underworld is divided in two parts: Erebus and Tartarus (the deeper). Edith Hamilton, in her book Mythology: Timeless Tales of Gods and Heroes, wrote that "In Homer the underworld is vague, a shadowy place inhabited by shadows. Nothing is real there. The ghosts' existence, if it can be called that, is like a miserable dream. The later poets would define the world of the dead more and more clearly as the place where the wicked are punished and the good rewarded.

One of the great imagery of the underworld has to do with Charon, the ferryman who ferries the soul of the dead across to the gates of Tartarus. Those very gates are guarded by Cerberus, a three-headed dog. Three judges decide the fate of the dead's soul. "Sleep, and Death, his brother, dwelt in the lower world. Dreams too ascended from there to men." Somewhere in the interior of the underworld lays Hades palace. Which brings us back to Persephone.

Persephone, was the daughter of Zeus and Demeter, the goddess of the harvest and agriculture, responsible for the fertility of the earth. Demeter kept her daughter from the different suitors who intended to marry Persephone. Hades, nonetheless, harvested such deep amazement for her that, upon being rejected Persephone's hand by Demeter, he planned to rapt her. One day Persephone was in a valley and stopped to contemplate a specially beautiful narcissus. Her companion had been separated from her and, as she kneeled down to pick the flower, the earth opened up and Hades rapted her, taking her to the underworld with him in a chariot drawn by black horses.

The only witnesses of the rapt were Zeus (brother to Hades) and Helios, the god of the Sun, but no one told Demeter about her daughter's fate. For nine days she roamed the earth, refusing to drink ambrosia, until Hecate advised her to ask Helios, who in turn took pity in her and told Demeter that Persephone was living in the underworld, as the wife of Hades. To grief, she left Olympus and wandered earth disguised as a mortal, and refused to do her duty, which lead to a barren, fruitless earth that devastated mankind. Zeus then decided to bring Persephone before them. If she showed she was being held against her will, she would return to Olympus with her mother. Hades, knowing this, made Persephone, who had been crying in despair, eat pomegranate seed which would make her long for the underworld.

A final decision was reached: Persephone would spend four month with Hades in the underworld, and six months with her mother. Demeter was full of sadness and mournful when Persephone was away from her, thus unable or unwilling to perform her duty and make the earth fertil. These months became part of Autum and Winter. The eternal cycle of death and rebirth was then created. There's a great component of death and rebirth embedded in this myth.

This myth is one of the first stories that include seasons as a device to employ in storytelling. The seasons have featured greatly in art (literature, specially) as a way to emphasize the message trying to be conveyed by the writer. Its uses are vast: it can canvey symbolism (even be used allegorically), it can reveal character, it can emphasize themes...

Thomas C. Foster, in his book How to Read Literature like a Professor, writes that, in a very basic archetypical way, we understand that every season carries certain connotations: "Maybe it's hard-wired into us that spring has to do with childhood and youth, summer with adulthood and romance and fullfillment and passion, autumn with decline and middle age and tiredness but also harvest, winter with old age and resentment and death." He adds that "we read the seasons in them (books and poems) without being conscious of the many associations we bring into that reading."

This goes way back; this archetype shows itself in a myth as old as Persephone's Rapt. Vivaldi wrote Le quattro stagioni (The Four Seasons), which is considered one of earliest examples of music with a narrative element; which, in this case, leans on the symbolism offered by each season. It is an ode to the four seasons.

But it's not about them; not really. Again, we come to Thomas C. Foster, who wrote that artists, employ symbolism, voluntarely or not, to help tell something to their audience. We should develop, he insists, a predisposition to "see things as existing in themselves while simultaneously also representing something else". Summer is literally the name of the character whom the protagonist falls in love with in 500 Days of Summer. She represents love, infatuation, romance, happiness. Walt Whitman makes use of seasons to help explain his approach and celebration of life. In the poem These I Singing in Spring, we can read verses full of symbolic force:

Here, some pinks and laurel leaves, and a handful of sage,

And here what I now draw from the water, wading in the pondside,

(O here I last saw him that tenderly loves me, and returns again never to separate from me,

And this, O this shall henceforth be the token of comrades, this calamus-root shall,

Interchange it youths with each other! let none render it back!)

And twigs of maple and a bunch of wild orange and chestnut,

And stems of currants and plum-blows, and the aromatic cedar

William Sheakspeare did it best. Sonnet 18 uses all the symbolism surrounding summer to express how, although it is the season that most comes close to descibe the dephs of his admiration, it ultimately fails. The verse But thy eternal summer shall not fade is one of the most significant, using summer directly as a metaphor to express life itself.

Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate:

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer's lease hath all too short a date:

Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines,

And often is his gold complexion dimm'd;

And every fair from fair sometime declines,

By chance, or nature's changing course, untrimm'd;

But thy eternal summer shall not fade

Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow'st;

Nor shall Death brag thou wander'st in his shade,

When in eternal lines to time thou grow'st;

So long as men can breathe or eyes can see,

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

Otoño (Autumn), by the uruguayan poet Mario Benedetti, is one the finest examples of use of seasons, adapting their traditional meaning they carry to explain his feeling of nostalgia and contemplation of the last years of his life:

Aprovechemos el otoño

antes de que el invierno nos escombre

entremos a codazos en la franja del sol

y admiremos a los pájaros que emigran

ahora que calienta el corazón

aunque sea de a ratos y de a poco

pensemos y sintamos todavía

con el viejo cariño que nos queda

aprovechemos el otoño

antes de que el futuro se congele

y no haya sitio para la belleza

porque el futuro se nos vuelve escarcha

The verse antes de que el invierno nos escombre (befor the winter takes us away) uses winter as a representation of death, the last season of life before death.

The examples of this are infinite.

Nonetheless, the problem with the earlier list of connotations for each season is that it is inherently limited. "People expect (symbols) to mean something. [...] Some symbols have a relatively limited range of meaning, but in general a symbol can't be reduced to standing for only one thing.", wrote Thomas C. Foster. In this case, and although the use of seasons in arts have had a relatively standard use, it would be simplistic to link all use of seasons as symbols as the bearer of the meaning intended in Persephone's myth (Winter as death, infertility, sadness, longing; Summer as life, fertility, happiness, reunion). Which is good (the fact that you can't pin down a symbol to a unique meaning). Foster writes: "That would be easy, convenient, manageable for us. But that handiness would result in a net loss: the novel would cease to be what it is, a network of meanings and significations that permits a nearly limitless range of possible interpretations".

Each season, too, have several weather conditions more or less connected with them (clear skies in summer, snow in winter, rain in spring, falling leaves in autumn) which, in turn, become symbols that are used to enforce even more the story and message that the artist is trying to communicate to his/her readers, listenenrs, etc. The areas that carry symbolism, of course, is also limitless. Geography and location can provide it; so can trips, simple actions such as eating together or violence.

But, taking historical meaning (of seasons, in this case) into consideration can illuminate your experience when delving into artistic expressions.

(*) The Underworld was the kingdom of the dead, located somewhere beneath the earth -you could find entrances throught caves, for example-, and it was ruled by Hades. The Underworld is sometimes refered simply as Hades. The Underworld is divided in two parts: Erebus and Tartarus (the deeper). Edith Hamilton, in her book Mythology: Timeless Tales of Gods and Heroes, wrote that "In Homer the underworld is vague, a shadowy place inhabited by shadows. Nothing is real there. The ghosts' existence, if it can be called that, is like a miserable dream. The later poets would define the world of the dead more and more clearly as the place where the wicked are punished and the good rewarded.

One of the great imagery of the underworld has to do with Charon, the ferryman who ferries the soul of the dead across to the gates of Tartarus. Those very gates are guarded by Cerberus, a three-headed dog. Three judges decide the fate of the dead's soul. "Sleep, and Death, his brother, dwelt in the lower world. Dreams too ascended from there to men." Somewhere in the interior of the underworld lays Hades palace. Which brings us back to Persephone.

Persephone, was the daughter of Zeus and Demeter, the goddess of the harvest and agriculture, responsible for the fertility of the earth. Demeter kept her daughter from the different suitors who intended to marry Persephone. Hades, nonetheless, harvested such deep amazement for her that, upon being rejected Persephone's hand by Demeter, he planned to rapt her. One day Persephone was in a valley and stopped to contemplate a specially beautiful narcissus. Her companion had been separated from her and, as she kneeled down to pick the flower, the earth opened up and Hades rapted her, taking her to the underworld with him in a chariot drawn by black horses.

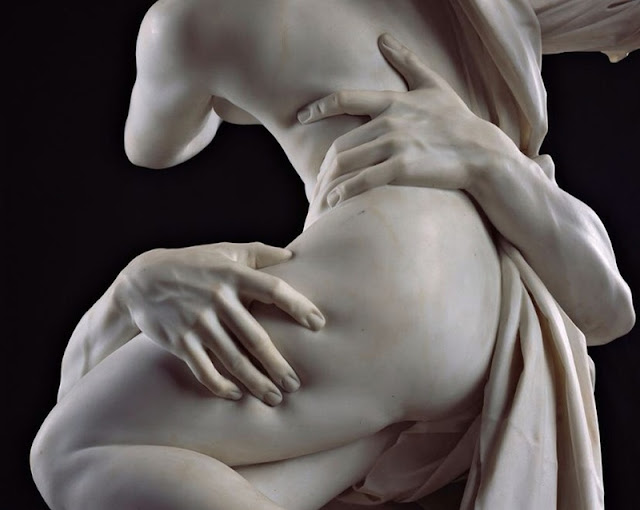

|

| The Rape of Proserpina Sculpture by Gian Lorenzo Bernini (which is the Roman version of the Myth of Persephone) |

The only witnesses of the rapt were Zeus (brother to Hades) and Helios, the god of the Sun, but no one told Demeter about her daughter's fate. For nine days she roamed the earth, refusing to drink ambrosia, until Hecate advised her to ask Helios, who in turn took pity in her and told Demeter that Persephone was living in the underworld, as the wife of Hades. To grief, she left Olympus and wandered earth disguised as a mortal, and refused to do her duty, which lead to a barren, fruitless earth that devastated mankind. Zeus then decided to bring Persephone before them. If she showed she was being held against her will, she would return to Olympus with her mother. Hades, knowing this, made Persephone, who had been crying in despair, eat pomegranate seed which would make her long for the underworld.

A final decision was reached: Persephone would spend four month with Hades in the underworld, and six months with her mother. Demeter was full of sadness and mournful when Persephone was away from her, thus unable or unwilling to perform her duty and make the earth fertil. These months became part of Autum and Winter. The eternal cycle of death and rebirth was then created. There's a great component of death and rebirth embedded in this myth.

This myth is one of the first stories that include seasons as a device to employ in storytelling. The seasons have featured greatly in art (literature, specially) as a way to emphasize the message trying to be conveyed by the writer. Its uses are vast: it can canvey symbolism (even be used allegorically), it can reveal character, it can emphasize themes...

Thomas C. Foster, in his book How to Read Literature like a Professor, writes that, in a very basic archetypical way, we understand that every season carries certain connotations: "Maybe it's hard-wired into us that spring has to do with childhood and youth, summer with adulthood and romance and fullfillment and passion, autumn with decline and middle age and tiredness but also harvest, winter with old age and resentment and death." He adds that "we read the seasons in them (books and poems) without being conscious of the many associations we bring into that reading."

This goes way back; this archetype shows itself in a myth as old as Persephone's Rapt. Vivaldi wrote Le quattro stagioni (The Four Seasons), which is considered one of earliest examples of music with a narrative element; which, in this case, leans on the symbolism offered by each season. It is an ode to the four seasons.

|

| Antonio Vivaldi |

But it's not about them; not really. Again, we come to Thomas C. Foster, who wrote that artists, employ symbolism, voluntarely or not, to help tell something to their audience. We should develop, he insists, a predisposition to "see things as existing in themselves while simultaneously also representing something else". Summer is literally the name of the character whom the protagonist falls in love with in 500 Days of Summer. She represents love, infatuation, romance, happiness. Walt Whitman makes use of seasons to help explain his approach and celebration of life. In the poem These I Singing in Spring, we can read verses full of symbolic force:

Here, some pinks and laurel leaves, and a handful of sage,

And here what I now draw from the water, wading in the pondside,

(O here I last saw him that tenderly loves me, and returns again never to separate from me,

And this, O this shall henceforth be the token of comrades, this calamus-root shall,

Interchange it youths with each other! let none render it back!)

And twigs of maple and a bunch of wild orange and chestnut,

And stems of currants and plum-blows, and the aromatic cedar

William Sheakspeare did it best. Sonnet 18 uses all the symbolism surrounding summer to express how, although it is the season that most comes close to descibe the dephs of his admiration, it ultimately fails. The verse But thy eternal summer shall not fade is one of the most significant, using summer directly as a metaphor to express life itself.

Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate:

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer's lease hath all too short a date:

Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines,

And often is his gold complexion dimm'd;

And every fair from fair sometime declines,

By chance, or nature's changing course, untrimm'd;

But thy eternal summer shall not fade

Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow'st;

Nor shall Death brag thou wander'st in his shade,

When in eternal lines to time thou grow'st;

So long as men can breathe or eyes can see,

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

Otoño (Autumn), by the uruguayan poet Mario Benedetti, is one the finest examples of use of seasons, adapting their traditional meaning they carry to explain his feeling of nostalgia and contemplation of the last years of his life:

Aprovechemos el otoño

antes de que el invierno nos escombre

entremos a codazos en la franja del sol

y admiremos a los pájaros que emigran

ahora que calienta el corazón

aunque sea de a ratos y de a poco

pensemos y sintamos todavía

con el viejo cariño que nos queda

aprovechemos el otoño

antes de que el futuro se congele

y no haya sitio para la belleza

porque el futuro se nos vuelve escarcha

The verse antes de que el invierno nos escombre (befor the winter takes us away) uses winter as a representation of death, the last season of life before death.

Nonetheless, the problem with the earlier list of connotations for each season is that it is inherently limited. "People expect (symbols) to mean something. [...] Some symbols have a relatively limited range of meaning, but in general a symbol can't be reduced to standing for only one thing.", wrote Thomas C. Foster. In this case, and although the use of seasons in arts have had a relatively standard use, it would be simplistic to link all use of seasons as symbols as the bearer of the meaning intended in Persephone's myth (Winter as death, infertility, sadness, longing; Summer as life, fertility, happiness, reunion). Which is good (the fact that you can't pin down a symbol to a unique meaning). Foster writes: "That would be easy, convenient, manageable for us. But that handiness would result in a net loss: the novel would cease to be what it is, a network of meanings and significations that permits a nearly limitless range of possible interpretations".

Each season, too, have several weather conditions more or less connected with them (clear skies in summer, snow in winter, rain in spring, falling leaves in autumn) which, in turn, become symbols that are used to enforce even more the story and message that the artist is trying to communicate to his/her readers, listenenrs, etc. The areas that carry symbolism, of course, is also limitless. Geography and location can provide it; so can trips, simple actions such as eating together or violence.

But, taking historical meaning (of seasons, in this case) into consideration can illuminate your experience when delving into artistic expressions.

Comments

Post a Comment